By Steve Hudspeth in Good Morning Wilton on June 6, 2023

On Saturday, June 10 at 4 p.m. at the Wilton Historical Society, an important event will take place: a Witness Stone will be dedicated for the first time in Wilton. Here is its significance.

How do you remember a life that history has obscured? In the case of those enslaved in Connecticut, slavery and poverty account for a lot of the “missing lives.”But skillful historical research can sometimes fill in the voids. When that happens, there can be a eureka moment — not one in which we know all that we’d like to know but enough to understand something of his or her life, its struggles and accomplishments, and to put it into the context of those times. The results put real flesh on otherwise little-known bones.

So how do we learn all that we can about people who seem lost to history? That’s where careful research comes into play, and fortunately in Wilton, we have the very skilled historical researcher Julie Hughes, Ph.D. She is the archivist of the Wilton Library’s Carol and Robert Russell Wilton History Room and its impressive collection of materials from the archives of the Wilton Historical Society as well as from the Library’s own collections. Her ability to tease fascinating historical information from obscure documents has become legendary in our region.

So, where does a researcher go to identify slaves in a household? Wills provide a very solid source of information, though the enslaved person may be identified as no more than “one wench.” Bills of sale for enslaved persons can also help, though again the record may not identify the person except as to gender, approximate age, and capabilities (size and strength for farm work for men, household skills such as cooking and sewing for women). Court records are also at times a very good source of information about present or formerly enslaved people who intersected with the courts in civil suits or criminal matters. Land records and census data can also be useful. Scouring of all of these types of sources has yielded much information in the case of one specific person here in Wilton whose life spanned both enslavement and emancipation.

Very unusually for formerly enslaved people of his time, John C. Wally owned his own home right here in Wilton. He served as a slave with the Abbott family from his birth to his enslaved mother in around 1800 until he turned either 21 or 25 depending upon his exact birthdate. (Under Connecticut’s 1784 emancipation law, slavery ended on a very gradual basis between 1784 and 1848 based in part on birthdate; the last enslaved person in Wilton was finally freed in 1848.)

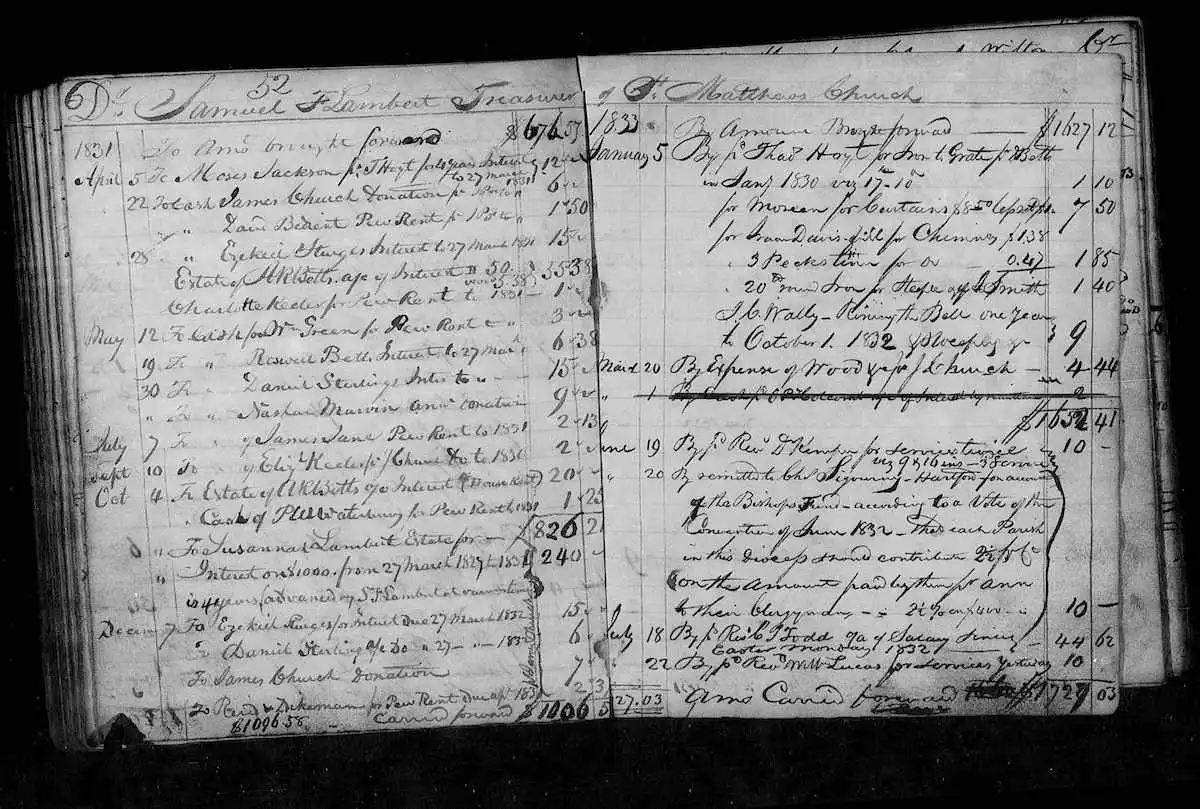

After his emancipation, Wally did a variety of types of work including at St. Matthew’s Episcopal Church here in town where he swept its floor, rang its bell, and started its warming fire on Sunday mornings (for an annual salary of $9). Other work he did included tending horses for Daniel Betts who lived across the street from what became Wally’s home. Betts seems to have been a friend to Wally.

In fact, Wally’s home is still standing though it has been added onto extensively since the time when he owned it. How he came to own that home remains an open question: Was it a gift, a sale, or a payment for services rendered? Betts’ Will describes the house as a gift to Wally, but that reference may have been included to assure that Wally was actually able to retain the home after Betts’ death. Did Wally face attempts to have the home taken from him? If so, how did he avoid that outcome? In any event, Wilton land records indicate that Wally received a payment on the sale of the house that was three times its value when he first came into ownership of it.

Wally’s life after he left Wilton was also a mystery until very recently, when more historical detective work enabled the identification of the place to which he moved after he left Wilton: namely Bridgeport, where his name appears on land records. In Bridgeport at that time there was a successful community of formerly enslaved people. However, it appears that Wally was not a part of that community in the sense of living there but may nonetheless have had regular dealings with its members. Death records indicate that Wally died in Bridgeport on January 22, 1859; his burial site is unknown, though the burial sites in Bridgeport of his wife Harriet and daughter Betsey have been identified. It is not known what happened to his son Samuel Solomon Wally (who was baptized at St. Matthew’s).

All of this information has been garnered over multiple months by painstaking research into the life of one formerly enslaved person. So, with it all now in hand, what can be done? The answer has been provided by St. Matthew’s joined by Westport’s Unitarian Universalist Congregation and Norwalk’s St. Paul’s on the Green and partially funded by the Episcopal Diocese of Connecticut. These congregations, and especially their youth and leaders, were trained by the nonprofit Witness Stones Project, Inc. about slavery in general and about the specifics of reading primary source documents such as Dr. Hughes’ research has identified.

To commemorate John C. Wally, a Witness Stone will be placed at the Wilton Historical Society to acknowledge Wally’s personhood along with that of the other enslaved and formerly enslaved individuals who lived right here in Wilton. They numbered in the hundreds over the two centuries that slavery persisted here in our own backyard — not just on distant Southern plantations.

We can all join in this recognition and acknowledgement process by attending the dedication of the Witness Stone on Saturday, June 10 at 4 p.m. at the Wilton Historical Society. The ceremony will include tributes prepared by the youth who worked so effectively and with such dedication on this highly significant memorial project.