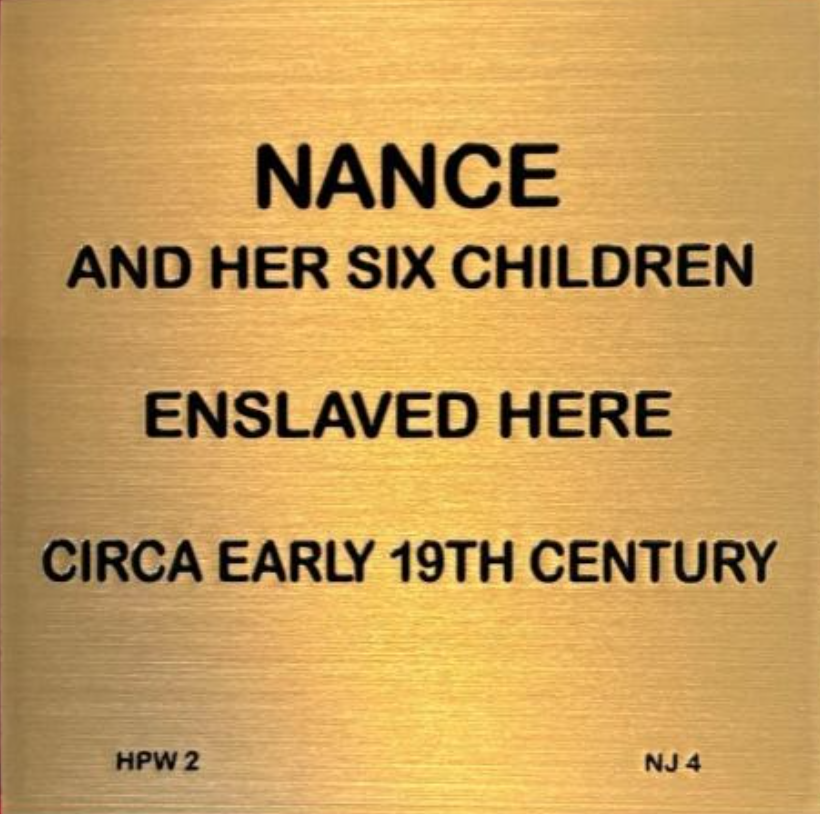

From Narrative of Nance’s Life by Student Corinne Saindon

Nance, most likely born around 1785 based on a record saying she was 65 in 1850, was an enslaved woman presumably born into slavery. While not much is known about her life, it can be inferred what it was like on the Phillips’ farm. Her work was probably focused in the kitchen and livestock areas and may have included cooking for the Phillips family. The kitchen space, which was hidden behind the main house, was cramped and dark without much space for smoke in front of the fire from the hearth to air out.

The space Nance was most likely allowed to live in was just above the kitchen, and also cramped, especially considering that she had to live there with her six children. Nance’s less-than-adequate living and working space is a reflection of the overall treatment of the enslaved, and how the masters could treat their slaves however they wanted to. Nance’s work may have also involved working with the wool from the sheep, turning it into yarn. The Phillips farm most likely had 16 sheep and 4 lambs during the time Nance was enslaved there, so it is within reason to believe that they were involved in Nance’s work. As previously mentioned, Nance gave birth to six children from 1808 to about 1824, when Nance was 23 to around 39. While the father(s) are unknown, the children’s names and births were recorded by William Phillips. In order from oldest to youngest, the children’s names were Zillah (1808), Charles (1810), Gus (1813), Elias (1817), Robert (1821), and Maria Ann (1824/1825) (Hunterdon County). The lack of ability for Nance to register her children is an example of the paternalism that was prevalent throughout the slave-holding states. This means that enslaved people were thought of as unable to do the same things as their free white masters, and were therefore thought to be needed to be taken care of and told what to do. Nance likely continued to help maintain the property up until the 13th

Amendment abolished either slavery in 1865 or her death, the date of which is unknown. After slavery was abolished, the Phillips’ farm property began to trade hands more and more, showing just how much the farm’s handling was dependent on the family’s enslaved people.

Nance’s Legacy

While Nance herself may not have been given the chance to receive the freedom she deserved, her children did get this chance. Since all of them were born after 1804 when the Gradual Emancipation Act was passed, which allowed enslaved females to be freed after 21 years and enslaved males to be freed after 25 years, they all were able to legally apply for their freedom and live out a majority of their lives as free people. During this time, free black communities began to appear within the Pleasant Valley area. Nance’s children, along with many other formerly enslaved people were able to show agency and resistance by aspiring to live the lives of free people in a society that was only beginning to recognize that slavery was wrong.

Nance, like so many other nameless and faceless enslaved people, did not receive the recognition she deserved for her hard life of oppression and maltreatment. It is important to simply acknowledge these people and the lives of unrewarded labor that many of them lived through. Showing agency through projects similar to this shines a new light on people whose stories would have otherwise stayed in the darkness. Nance’s life was one led by many people, often against their will, and often passed onto their children in a constant cycle of abuse and exploitation to feed the capitalistic society that was the emerging United States of America. Slavery as a whole was a practice that encouraged the purposeful mistreatment of a group of people based on false beliefs that they were entirely worth less than white people. The importance of sharing these stories is not only to prevent things like this from happening again, but also to show respect and honor those whose legacies would have otherwise been forgotten.