By Kendra Baker in News-Times on June 18, 2023

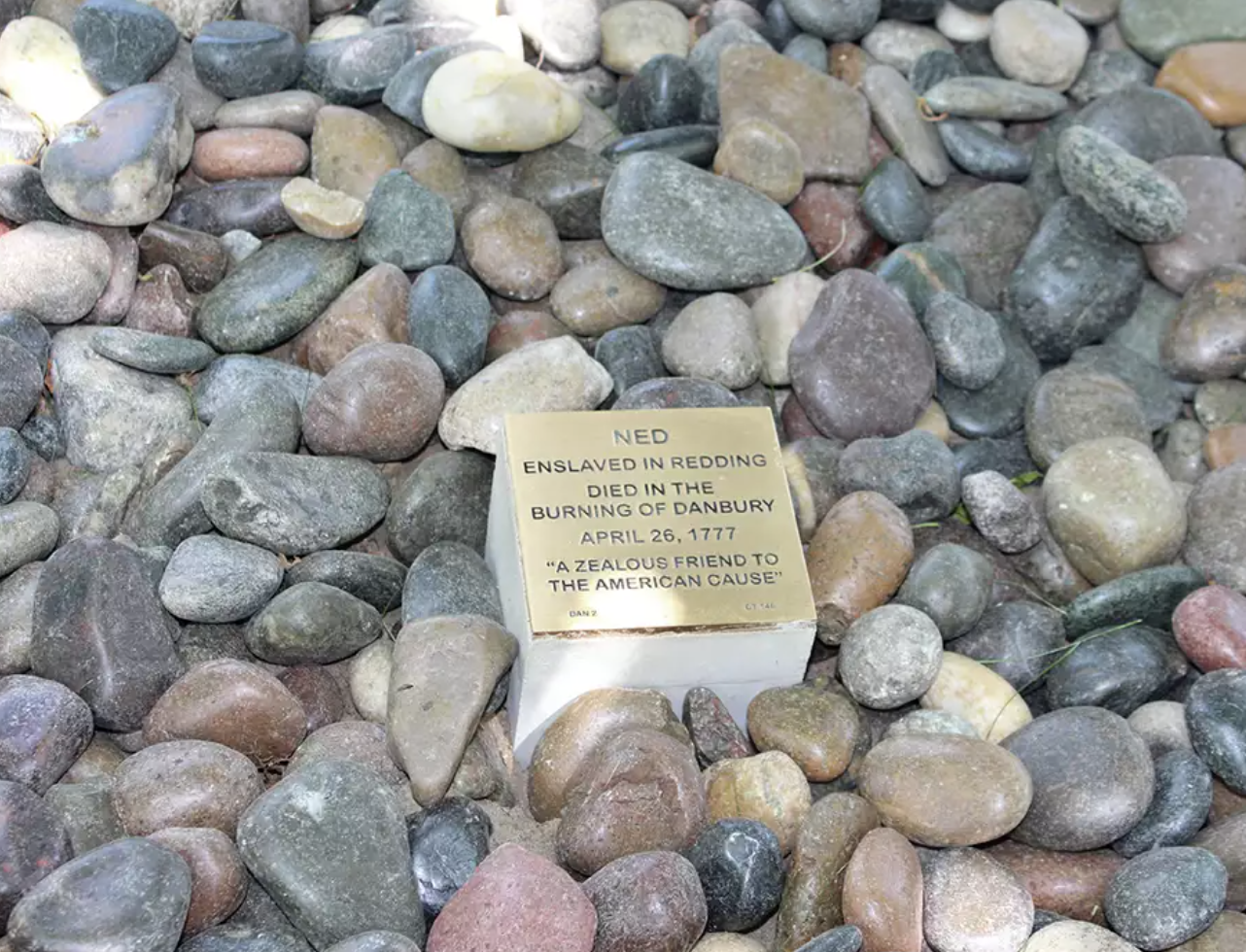

DANBURY — The life Ned, an enslaved man killed in 1777 when British soldiers burned down Danbury, has been memorialized as part of a student-led research project.

A stone commemorating Ned was placed at the Wooster School campus on May 30, following weeks of research by the school’s eighth grade team in partnership with the Witness Stones Project. The Witness Stones Project works with schools and community groups to “restore the history and honor the humanity” of enslaved individuals in Connecticut through research, education and civic engagement.

Wooster School has been working with the organization for the past two years to teach students about the history of slavery in Connecticut. As part of the curriculum, students embark on a research project that culminates with the memorialization of formerly enslaved individuals from the area.

Last year, students installed the first Witness Stone in Danbury in honor of a resident named Nimrod, who was born into slavery in the 18th century, served during the Revolutionary War and died a free man. His stone was placed at the Long Ridge United Methodist Church.

For this year’s project, eighth graders spent at least two months researching Ned before memorializing him with a stone installed on the Wooster School campus.

“The students did a lot of work,” said Joulé Bazemore, Wooster School’s Equity and Justice Center director. They used a number of primary resources to not only research Ned, but also to examine the treatment of enslaved individuals, as well as their agency and resistance against the practice of enslavement.

Through their research, students learned that Ned was enslaved by a Redding man named Samuel Smith, who had “hired him out to a family in Danbury” — and that’s why Ned was there when British soldiers raided the city on April 26, 1777, Bazemore said.

“As the British were coming through Danbury, they encountered Ned and several other people, and Ned lost his life in that fight,” Bazemore said.

Ned was killed at the home of Maj. Daniel Starr after he and a few other men reportedly opened fire on British troops from inside the residence.

While some accounts of the events that unfolded refer to the enslaved man as “Adams,” Bazemore said based on the students’ research, they believe “maybe Adams was Ned.”

“The challenge with this type of project is that there’s only records when people have a stake in producing the information,” she said. “The reason why we were able to get information on Ned was because the Smith family wanted to be paid for their loss of property.”

In addition to probate and other records kept by the Smith family, Bazemore said the students looked at court testimony related to a petition the family filed for reimbursement of “lost property” after Ned’s death.

Ned became the focus of Wooster School’s second Witness Stones research effort at the suggestion of Witness Stones Project Operations Director Liz Lightfoot, who Bazemore said had been researching Gen. David Wooster and came across Ned’s story.

A few days after Ned’s death, British soldiers encountered Wooster and his men on their way to Redding. The Battle of Ridgefield ensued, and Wooster wound up dying from injuries on May 2, 1777.

“Not long after Ned lost his life, General Wooster lost his,” Bazemore said. The students explored the question of why certain people — particularly in turning points of history — are “amplified” while others are not, she said.

“General Wooster was amplified because he was a general, and we hold these people in high esteem. But Ned, being an enslaved individual, we don’t hear their stories as often,” she said. “We wanted to highlight that.”

In the biography of Ned that they wrote as part of the project, the Wooster eighth graders noted that while Gen. Wooster is widely recognized for his role in the American Revolution and has towns, schools and parks named after him, that is not the case for Ned — but it should be, they said.

“We need to honor the black heroes from the Revolutionary War more than we do,” the students wrote. “Wooster was greatly recognized for all he did, and he died near the same place Ned died, so why can’t we honor Ned for all he did for this country?”

Given the school’s ties to Gen. Wooster and the question posed to students about different historical acknowledgement of people, Bazemore said they decided to install Ned’s Witness Stone on the Wooster School campus.

“We need to honor Ned’s death because he is one of the heroes that helped America become what it is today who hasn’t been recognized or honored yet,” the students wrote in their biography. “Ned is an American hero because he didn’t let slavery stop him from fighting for what he truly believed in.”

In addition to memorializing Ned, Bazemore said his Witness Stone is a reminder that there are notable stories like his that are not widely known.

“There are schools right now in our nation that cannot teach any of these things, but we do have Ned’s stone here, where the kids can see it and we can talk about him,” she said. “Unpacking what slavery looked like isn’t something to be shameful of. We need to embrace and say, ‘OK, what can we learn from this and how can we make changes moving forward?’”

The Witness Stones Projects allow students to engage in “important social impact work” through which they not only learn about history, but amplify the lives of those whose stories have gone untold, Bazemore said.

“Our goal is always to put student learning first, and this allows them to do the research, ask questions, present their research — and they get to bring people to life,” she said. “One of my colleagues said he felt this was the most important work that we’ve ever done as a community, and I agree with him. This is important.”