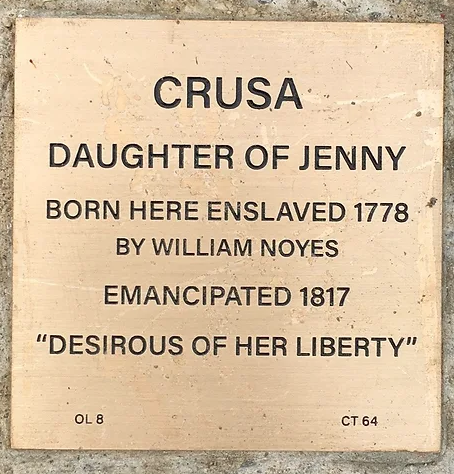

A Noyes family scrapbook notes that Crusa was born Sept. 17, 1778. The fourth child of Jenny and Prince, Crusa served William Noyes in the house that stood on the site of today’s Florence Griswold Museum. After his death, she passed to his son William Noyes Jr. A certificate titled Emancipation of Crusa a Negro, signed on January 7, 1817, and entered into the land records, includes William Noyes Jr.’s statement granting “my female slave Crusa” her “full liberty & free whatsoever she pleases and to act in all respects as any free person can.” Crusa was then 39.

A Noyes family scrapbook notes that Crusa was born Sept. 17, 1778. The fourth child of Jenny and Prince, Crusa served William Noyes in the house that stood on the site of today’s Florence Griswold Museum. After his death, she passed to his son William Noyes Jr. A certificate titled Emancipation of Crusa a Negro, signed on January 7, 1817, and entered into the land records, includes William Noyes Jr.’s statement granting “my female slave Crusa” her “full liberty & free whatsoever she pleases and to act in all respects as any free person can.” Crusa was then 39.

The certificate states that after an “actual examination” of Crusa’s circumstances, Lyme’s civil authorities found her in good health and were convinced that sd Slave was desirous of her liberty at this time. The language used to certify her emancipation reflects specifications in a Connecticut law enacted in 1792. Provided that a slave, based on an actual examination, was not younger than twenty-five or older than forty-five, was in good health, and was “desirous” of being set free, local authorities could certify the slaveholder’s exemption from financial responsibility for the formerly enslaved person.

No subsequent reference to Crusa in Lyme has been found, but in 1824 the firm of Minard & Noyes, which sold sundries in nearby Salem, billed a colored woman named Cruse, so perhaps she lived there after being set at liberty.