Location: 34 North Main Street, West Hartford, Connecticut

The Life and Times of Jude of the West Division

A student essay by Jaza Amchok, Janelle Isaacs, Asjha Malcolm, Cameron Slocum, Thomas Wilson, Xiao Xin Xie

The northeast is often portrayed as free and progressive on the issue of slavery. Northerners are considered the “good guys.” Strolling through the Newington Green, along the Farmington Shoppes, and walking through West Hartford Center, it is easy to buy into this image of the north. It is altogether astounding that slavery should exist for almost two hundred years, and yet there is almost no mention of it in the history of northern states, especially since government reports suggest that New England merchants were exporting enslaved people from Barbados in the late 1600s.

By 1709, it was recorded that 110 black and white servants resided in Connecticut; and by 1730, the Connecticut colony had a black population of 700 out of the 38,000 people. Between 1756 and 1774, the ratio of enslaved people to freedmen in Connecticut dramatically increased.

As colonial leaders established their economic reasons for slavery in New England, many colonies began to pass laws institutionalizing this system. In parts of Connecticut, such as the West Division of Hartford, owning an enslaved person also denoted wealth and status. Many of these enslaved people were owned by merchants, shopkeepers, and ministers.

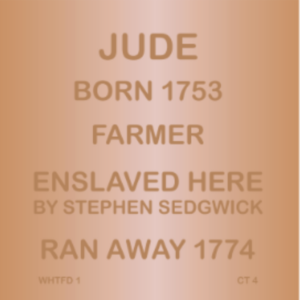

Unfortunately, research on local enslaved people is limited, but when historians can piece together information about a particular enslaved person, it can illuminate this oppressive system. Recent discoveries have reignited inquiries about enslaved people living in West Hartford, specifically about a man named Jude. Jude, born circa 1753, was passed down in his will from Stephen Sedgwick, Sr. to Stephen Sedgwick, Jr. after his death in 1768. By learning about his life and the time during which he lived, one more piece is located in the puzzle of colonial West Hartford.

Slavery in Connecticut

Slavery in the northeast was a complicated issue. Although the North is touted for its progressivism and acceptance of people of African descent, underlying racism still allowed slavery to persist for over two hundred years in Connecticut. One well-documented case of slavery in the state stems from an enslaved person named Venture Smith, who published an autobiography in 1798 in New London, CT. According to Smith’s autobiography, slavery in the North was by no means easy in comparison to the South. Enslaved people were mistreated, and often clubbed for mistakes they made. Furthermore, it was not uncommon for masters to take the savings of their enslaved people when they misbehaved. The Black Code, a series of laws passed between 1690 and 1730, further restricted the rights of the enslaved. According to Connecticut colonial law, enslaved people were required to carry passes with them when they left town, they could not drink alcohol, they could not sell items without their master’s permission, and they had a curfew of 9 p.m. The most common punishment for breaking these rules was whipping. Not only that, enslaved people were expected to follow Christian principles by attending the same church as their master, as indicated by church records.

One positive aspect of the Black Code is that former masters had to provide support for their freed slaves, if necessary. Since freed enslaved people often were not capable of providing for themselves immediately after being freed, this law was beneficial to them. On top of that, if a master refused to help a freed person, the town would step in and provide for the enslaved person themselves.

By the time of the Revolutionary War, Connecticut had the largest number of enslaved people in New England. The largest increase in this population occurred between 1749 and 1774. New London County became the largest slaveholding section in New England, as it was an port and center of trade that accounted for about one-third of the enslaved people in Connecticut.

Focusing more closely on West Hartford, historians are confident that there were between twenty and thirty enslaved people in the West Division of Hartford during the late 18th and 19th centuries. The West Division of Hartford was established in the 1670s by the oldest families in Hartford and their progeny. Most settlers were farmers interested in acquiring large plots of land. Some of the West Division of Hartford’s most prominent families were the Perkins, the Goodmans, the Olmsteds, the Hookers, and the Sedgwicks.

The Sedgwicks, along with most of the other families in West Hartford at the time, derived their income primarily from agriculture, with corn, wheat, and flax being the largest crops at the time. Evidence unearthed when researching another West Hartford man, Bristow, suggests that West Hartford enslaved people most likely would have worked in the fields and the orchards or have performed tasks to ensure the household was in proper order, in addition to tending to any livestock that may be owned by their masters. And, those who owned people of African descent also seemed to be the leaders of the church and the town. The inventories of many of the prominent families include the terms “negro servant,” or “Negro boy.”

Church records also suggest that many of West Hartford’s enslaved people were members of the church and attended with their masters. One interesting thing to note is that according to primary source documents, following the Revolutionary War, many of the enslaved people started to be referred to as “a Man” or “a Woman” which suggests that quite a few West Hartford enslaved people were freed after the Revolution. For Jude, however, this does not appear to be the case.

The Sedgwick Family

The Sedgwick family is important to this narrative, because they owned Jude. The Sedgwicks were quite influential in the the West Division of Hartford, partially because Captain Samuel Sedgwick, most likely born in 1666, married Mary Hopkins. She was the granddaughter of John Hopkins, one of Hartford’s founders. Furthermore, the Sedgwicks’ wealth contributed to their prominence in the community. Samuel Sedgwick inherited money from his grandmother, Elizabeth Allen. Elizabeth Allen’s first husband, Rev. Samuel Stone, came to Hartford with Thomas Hooker and was the second minister of Hartford. After his death, Allen married George Garner in 1641, a merchant from Salem, Massachusetts, who owned the Stone Homestead. When he passed away in 1663, Elizabeth Stone inherited the Stone Homestead. When she died around 1681, Samuel Sedgwick inherited part of the Homestead with some money.

Samuel Sedgwick was one of the first Sedgwick’s to live in the West Division. Around 1685, Sedgwick moved to the West Division and purchased a large piece of land: approximately 273 acres in the West Division that stretched from the intersection of Main Street westward. He divided this land with Stephen Hopkins. The street going through his land later was named Sedgwick Road. In his day, it was called the “Road past John Seymours.” Samuel Sedgwick also owned more land in Farmington, a neighboring town.

Some of the land the Sedgwicks owned was sold over time, but they still controlled a lot of the land in the West Division. Additionally, the Sedgwicks are believed to have been involved in the production and sale of “cyder” and gin. According to Hathaway, in 1731, Samuel Sedgwick is thought to have been granted a license to sell “strong drink and keep a house of public entertainment of strangers,” or, to operate a tavern. Although it is not clear, his sons may have continued the business after his passing in 1735, and the street Gin Still Lane may have been named after the Sedgwick’s business. The tavern may also have played a role in the Sedgwicks increasing their wealth.

In his will, Samuel Sedgwick gave half of his house to his wife, Mary Hopkins. He also granted land to his sons. One of them, Stephen Sedgwick Sr., inherited 55 acres of land, taken from wherever he wished. Historians believe Stephen Sedgwick, Sr. chose a tract of land on the intersection of today’s Sedgwick Road and Mountain Road, including Spicebush Swamp. Although today Sedgwick’s house would be in West Hartford, during the 1700’s, his land was located just over the town border in Farmington.

Stephen Sedgwick, Sr. was well-off, like his father, as can be seen in an inventory taken after his death in 1768. According to Stephen Sedgwick’s inventory, they owned at least 110 acres of land, 20 cows, 45 sheep, 12 swine, 5 horses, 1 bull and 2 yoke of oxen. They owned a “cyder mill” and materials that distilled gin. They owned a Dutch wheel and sheep shears to make textiles.

In Sedgwick’s Probate Record, the enslaved man Jude is listed on a line which says “also my Negro boy Jude also all my cattle and all my Horses and all my sheep and all my swine.” This reinforced that he was property, not much more than the sheep that grazed their fields. Even as a boy, his owner would have been forced to work for the Sedgwick family.

After Stephen Sedgwick Sr.’s passing, it is believed that he willed Jude to his son, Stephen Sedgwick Jr., who later put out an ad for Jude after he ran away. The area in which Stephen Sedgwick lived was not as populated with other citizens compared to other areas of the West Division. Therefore, when Jude escaped, it might have been easy for him to leave unnoticed.

The Life of Jude

It is not known where Jude was born. We know he was born circa 1753. In the runaway notice in the Connecticut Courant from 1774, Jude is described as a mulatto, meaning he is of mixed race. During this time period it can be inferred that Jude had a white father and a mother of African descent. It is possible, as was often the case with enslaved people, that his white master had relations with his mother. In many cases, a master would force himself on his enslaved women, resulting in the birth of mixed-race children. Perhaps this was the case with Jude. Stephen Sedgwick, Sr. could possibly be the father of Jude. Seeing as Jude was born in 1753. Stephen Sedgwick, Sr. would have been 22 years old. At this age Stephen Sedgwick, Sr. could have very well started a non-consensual relationship with one of the enslaved women, Jude’s mother. By law, slavery was passed down maternally, Jude’s mother would most likely be of African descent.

For the Sedgwicks, who not only owned a cider mill but also owned more than 100 acres of land, Jude could have been assigned to pick apples during the fall to make the cider. In the spring and summer, he might have sheared sheep, milked cows, cultivated corn, wheat and flax, and did other handy work.

In August 1774, it was reported in the Connecticut Courant that Jude ran away at age 21. While the means by which he escaped remain unknown, it can be assumed that he ran because he did not want to be owned by anyone and felt he had the ability to live on his own.

There is not documentation of how Jude was treated by the Sedgwicks, but the fact that there was an advertisement documenting Jude’s escape, we can infer that he was not treated well and his status did not allow him all the freedoms and respect he felt he deserved. Some say that slavery in the North was not as brutal as slavery in the South, yet they were still owned and needed a pass to go places that could make an enslaved person in the North long for freedom. It is also important to note that Jude ran away carrying what likely was everything he owned: a “claret colored coat and waistcoat, light colored waistcoat, linen trousers, a good pair of leather breeches, three shirts, and his forged pass.” He ran away with what he could carry and what he felt was his, signifying his agency and his choice to leave. Stephen Sedgwick offered a $20 reward for his return.

What could Jude have done after he escaped? The area in which Stephen Sedgwick lived was not as populated compared to other areas of the West Division. Therefore, when Jude escaped, it might have been easier for him to leave unnoticed. There is no explicit answer, but based on the trends of other escapees from the time, Jude may have tried to gain his freedom by going further north to Canada or finding work in the ports on the Connecticut River. Those who were able to escape or were set free, often worked on the boats; therefore Jude would have fit in. While on the more negative side, another outcome would have been that Jude was recaptured by the Sedgwicks.

Though historical evidence regarding this period in West Hartford’s history is limited, historians are able to determine certain definite facts in order to piece together the life of the Sedgwick family’s enslaved person, Jude. In the West Division of Hartford, to own an enslaved person denoted their wealth and their status. While his life is difficult to fully understand over two hundred forty years later, it is clear that the life of Jude was replete with hardship, and through his perseverance, he sets an example that we would do well to follow today.

Bibliography

Bristow: Putting the Pieces of an African-American Life Together. West Hartford, CT: Noah Webster House & West Hartford Historical Society, 2006, https://noahwebsterhouse.org/past-exhibits/.

DeVaughn, Booker. “Remembering Bristow.” Connecticut Explored, 26 Oct. 2017, https://www.ctexplored.org/remembering-bristow/

Editors of Northeast Magazine. “The State that Slavery Built.” Hartford Courant, September 29, 2002.

Farrow, Anne et al. Complicity: How the North Promoted, Prolonged, and Profited from Slavery, Ballantine Books, 2006.

First Church of Hartford. “Church Records.” Ancestryclassroom.com. Last modified 1920.

First Church of West Hartford. “Church Records.” Ancestryclassroom.com. Last modified 1920.

Greene, Lorenzo J., The Negro in Colonial New England, 1620-1776. Columbia University Press, 1942.

“Runaway Slave Advertisements 1764-1800,” Connecticut Courant.

Hatheway, Elizabeth C. “A LOOK AT WEST HARTFORD CENTER IN 1776.” Noah Webster Foundation and Historical Society of West Hartford, June 1977.

“Jude Runaway Advertisement,” Connecticut Courant, August 9, 1774.

Parsons, David L. “Slavery in Connecticut 1640-1848.” Yale-New Haven Teachers Institute. http://teachersinstitute.yale.edu/curriculum/units/1980/6/80.06.09.x.html.

Sedgwick, Hubert Merrill, ed. “The Sedgwick Collection at the New Haven Colony Historical Society.” http://www.sedgwick.org/na/library/nhchs/boxo06/l/nhchs-b46-61-001.html.

Sedgwick, Stephen, “Probate Record,” 1768, in Ancestry.com/classroom.

Steiner, Bernard Christian. History of Slavery in Connecticut. Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins Press, 1893.

Strother, Horatio T. The Underground Railroad in Connecticut. Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 2011.

Sweet, John Wood. “Venture Smith from Slavery to Freedom.” Connecticut History.org. https://connecticuthistory.org/venture-smith-from-slavery-to-freedom/.

Taylor, Frances Grandy. “Connecticut’s Chattel Amnesia.” Hartford Courant (Hartford, CT), February 2001, Sec. D.

“The Timothy Goodman House (1750).” Historical Buildings of Connecticut. http://historicbuildingsct.com/the-timothy-goodman-house-1750/.

“Timothy Goodman Biography.” ancestryclassroom.com.

“Timothy Goodman Inventory, 1786,” Ancestryclassroom.com.

Town of West Hartford. “Old Center Cemetery.” West Hartford Connecticut. https://www.westhartfordct.gov/gov/departments/fairviewcemetery/oldcenter.asp.

U.S. Department of the Interior. “The Middle Passage.” National Park Service, https://www.nps.gov/articles/the-middle-passage.htm.

Whitman, Henry, “Slaves in West Hartford from Church Records,” Whitman Collection, Noah Webster House & West Hartford Historical Society, c. 1910.

“Will of Timothy Goodman.” Ancestry.com. Last modified 1786.

“Will of Stephen Sedgwick, Jr.” 1797. In Farmington, CT Probate. Ancestry.com.

“Will of Stephen Sedgwick, Sr., 1766.” 1766. Ancestry.com.

Wilson, Tracey M. “Bristow: A Man Who Bridged Cultures, and Bought His Way to Freedom,” Life in West Hartford: A Connecticut Community’s History, Noah Webster House & West Hartford Historical Society, lifeinwesthartford.org/.

______, “America Exposed as a Divided Society.”

______, “Putting the Pieces of an African American Life Together.”