By Sue Braden in CT Insider on November 14, 2024

GUILFORD — In 1773, Theophilus Morgan Jr. “gifted” 1-year-old slave “baby Rose” to his 9-year-old granddaughter Rebecca Parmelee, an act that was rare in Connecticut though fairly common in the South.

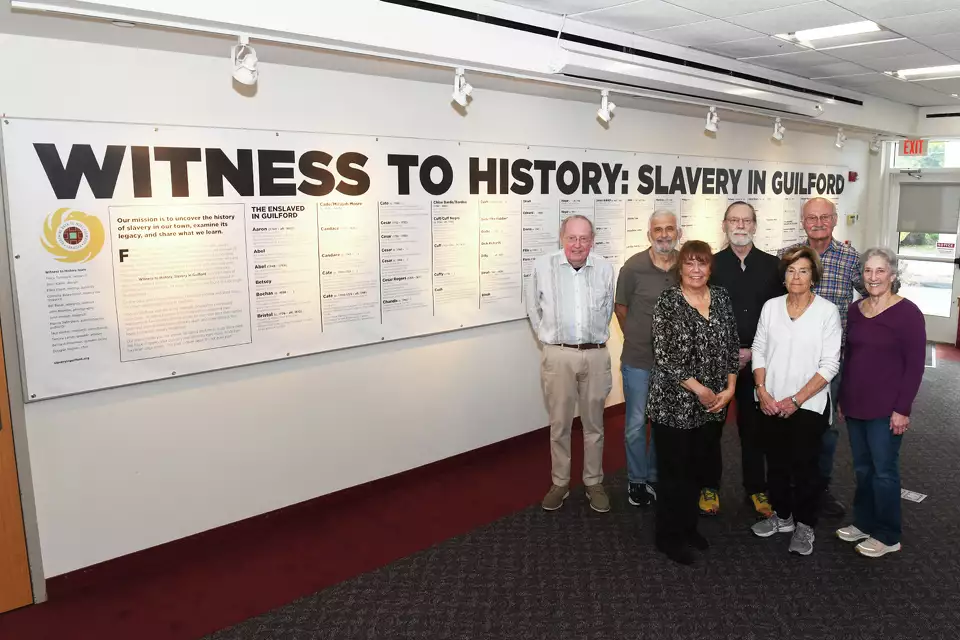

Baby Rose is among the 100 people who were enslaved in Guilford and are now being spotlighted in local historians’ effort to tell their stories in the new “Witness to History, Slavery in Guilford” project on view at the Guilford Free Library.

The display of names and a timeline sprawl across two long walls in the library through November.

While the stories are scant as very little information about the enslaved residents’ lives was recorded, their sheer number and bare facts tell a story.

Baby Rose lived with Parmelee and her family at what is now the Hyland House Museum, 84 Boston St.

Historian Tracy Tomaselli, who headed the project, likened the grandfather’s gift to “giving a child a live doll to play with.”

“For all the information we’ve uncovered with the Witness Stones Project, that’s the first time we see a child gifted to another child,” said Dennis Culliton, head of the Witness Stones Project.

He noted that caring for very young, enslaved children was costly for families.

“It’s like giving somebody something that’s going to be very expensive to maintain until you’re starting to gain value,” Culliton said. “But what we know about in the South, oftentimes children were gifted to other children as a helpmate or a playmate as they got older.”

Candace, a 23-year-old enslaved woman who lived in the household, most likely looked after Baby Rose, he said.

But in the case where the mother died, Culliton said the enslaved child was often given to the care of another enslaved woman.

Morgan deeded baby Rose to his granddaughter with the stipulation that should Parmelee die or not get married, the child would be passed on to her elder sister.

It was typical for women of the family to be given slaves, as they would bring the individuals as property into a marriage, Culliton noted.

The project at the library also shows two enslaved men who fought in the Revolutionary War: Shem, who was ultimately buried next to his enslavers, and Gad Asher, who later became the father-law of Guilford freeman Ham Primus, and fought in his owner’s stead in a trade to win his freedom.

Asher returned partially blinded from a war injury and learned his enslaver

now required him to pay 40 pounds for his freedom. Asher’s disability earned him a military pension though, which he used to buy his freedom in 1780, Culliton said.

Asher moved to North Branford and married a free Black woman but was misled believing that his children were also enslaved by his previous owner. He paid the enslaver for their freedom too, even though by law they were free, Culliton said.

The gravestone of Shem, who was buried next to his enslavers Submit and her husband Deacon Simeon Chittenden in the North Guilford Cemetery. Photo courtesy of Tracy Tomaselli.

Guilford held a large number of slaves relative to its population, Tomaselli said. East Guilford, now Madison, was included in the project.

Enslavers often held respectable positions. About half of Connecticut’s slave owners in 1774 were doctors, ministers and public ofcials, Tomaselli said. More than 6,500 people, or about 3.4 percent of the state’s population at the time were enslaved, more than any other state in New England.

Merchants, innkeepers and people involved in the shipping industry also held slaves, Tomaselli said.

Many enslaved people were sold or transported from the docks in Guilford, Culliton said. And afuent towns, as well as seaports, in the state had more slaves than other areas. Towns with productive farmland were reliant on slave labor as well, he said.

In 1784 the state passed laws for gradual emancipation with enslaved persons born after March 1, 1784, to be freed upon reaching age 25.

Tomaselli has theories about why slavery was so prevalent among the clergy here.

“Basically, the reverends were busy writing their sermons and preaching and ministering,” she said. “They didn’t have time to manage their farmland. So, they would need enslaved people to do that and household chores.”

She said she was surprised to learn most of the reverends did not free their slaves upon their deaths, And they were often given to their children who were not in the clergy or sold to others.

However, Rev. David Naughty, who enslaved Montros and Phillis in 1728, a couple who had several children, stipulated in his will that upon his wife’s death the family would be freed and given a plot of land and a yearly stipend of 10 pounds for life.

But his widow, Ruth Naughty, did not comply with his wishes when she died as “she enslaved the children for life and there’s no evidence that she gave them the 10 pounds,” Tomaselli said.

“Even Ruth Naughty in her will specically said that she didn’t do what her husband wished, but she wanted them to be in ‘good and godly homes,’” Tomaselli said. “But yet she didn’t give one of them to a reverend.”

Tomaselli said people where “sad and surprised” during her earlier presentation as “they stood here reading the names and the timeline.”

“I was overwhelmed,” said Janyce Siress, a library staffer. “It was just, it was just so provoking and just very emotional, and it’s so well done.”

The exhibit made the names come alive for her, and helped her envision them walking the same streets as her.

Tomaselli, a genealogist and president of the Guilford Preservation Alliance, said the program is a result of 10 years of painstaking research, combing through probate, birth, death and baptismal records, in addition to documents at the Whitfield House Museum, The Connecticut Museum and the National Archives.

What Tomaselli came away with is “Each is an individual. Each has their own story.”

“The number of enslaved people is a lot higher than we anticipated or expected to find,” she said. “And we are still discovering more through reading more probate records and more research.”

She wanted to do the program because the enslaved in town were largely a forgotten people. Historical gures are mostly town leaders, generals and clergymen, she said.

“So, growing up in Guilford and going through the school system here, I’m glad that the children now are being educated about this important part of Guilford’s history, this chapter in Guilford’s history, and that adults as well are learning about it.”

Tomaselli was deeply affected by the project, “There are deinitely feelings of remorse and that it’s sad that this happened. And it’s hard to put that into words.”